Privacy Preserving Machine Learning

For the common good, there is a need for techniques / knowledge allowing for machine learning models to be trained on the vast amount of private datasets held by medical facilities. Those datasets are currently not being shared for obvious privacy and legal reasons. Were those datasets made available, better predictive models (not biased ones tailored to one specific demographic) could be deployed for applications that truly matter such as chest X-ray analysis.

Summary - TL;DR

Andrew Trask’s 2 minute video introducing The Private AI Series courses.

Context

- Deep Learning Revolution (need for large labeled datasets) - New paradigm: Software 2.0

- Large amount of freely available (labeled) image data: ImageNet (dogs, cats, cars, planes, …)

- Lack of large freely available medical data (for applications that truly matter): not currently shared due to privacy and legal issues

- Transfer Learning

- Need for ways / techniques / knowledge to share sensitive data while keeping it private (medical images, genetic data, financial information)

Techniques aiming to allow the sharing of sensitive data while keeping it private

- Data anonymization - De-identification

- Differential Privacy

- Federated Learning

- Encrypted: Secure Multi Party Computation

- Encrypted: Homomorphic Encryption

Resources

- courses: Secure and Private AI (Udacity - OpenMined), The Private AI Series (OpenMined, Facebook AI, University of Oxford)

- Open Source Community: OpenMined.org: Lowering the barrier to entry to privacy preserving machine learning technologies

- Tools: OpenMined, PySyft, PyGrid, TensorFlow Federated, CrypTen, TenSEAL, SEAL

- Homomorphic Encryption standardization: homomorphicencryption.org

- Conferences: PriCon 2020, PPML @ NeurIPS

Context

The past few years have been very exciting with Deep Learning developments that saw entire domains of application being revolutionized, namely image processing, speech recognition and natural language processing. One of the reasons for those advancements is the availability of freely available and relatively large (labeled) datasets, such as ImageNet for image processing. (For information, the other reasons are significant increase in computing power and knowledge on how to train those deep models).

ImageNet is a collection of over 14 million images representing, among other types, animals, vehicles, buildings, people and food. Each of those images is classified using labels (nouns) from the WordNet ontology. Thanks to that unique database, one is able to train deep neural network models that can subsequently classify images in thousands of classes (from that WordNet ontology). With these new models, we are able, for example, to have the images that we take our smart phones be automatically labeled in at least a thousand different categories. This functionality comes in very handy when searching though our ever growing image libraries.

Thanks to transfer learning, those models, trained on ImageNet, can be re-used for applications that truly matter, namely for the health domain. In the past few years, we saw some great models being developed for X-rays classification (e.g. CheXNet), dermatology (e.g. skin cancer classification) and ophthalmology (e.g. diabetic retinopathy) to name a few. For other examples of medical applications, the book Deep Medicine by Eric Topol is highly recommended.

For privacy and legal reasons, large databases of medical images are not available for training the large models that we typical encounter in deep learning applications. The largest publicly available database of medical images contain only in the order of tens of thousands of images (e.g. NIH Chest X-ray dataset) which are insufficient to train a model without resorting to using ImageNet.

A relatively new field called Privacy Preserving Machine Learning aims to develop techniques allowing for the training of machine learning models on private data while guaranteeing, to various degrees, the privacy of such data. In essence, private and sensitive datasets can finally be used for the common good. Some of those techniques also permit the use of (encrypted) machine learning models to make predictions on encrypted data, and produce encrypted results. This comes in handy for ensuring privacy when used in sensitive domains such as the medical field.

Those privacy preserving techniques are (somewhat in order of increasing guarantee of privacy): 1. Data anonimization / de-identification, 2. Differential Privacy, 3. Federated Learning, 4. Secure Multi Party Computation, and 5. Homomorphic Encryption.

1. Data anonymization - De-identification

The first basic scheme aiming to share information while attempting to keep sensitive data private is data anonymization. The methods applied are based on techniques that we have known for many tens of years, namely building handcrafted rules to obfuscate information in an attempt to inhibit the possibility of re-identification of personal / private information.

As an example, consider the original document below (generated using OpenAI GPT-3) and its anonymised version. With data anonymisation, all references to named entities would be replaced with some generic (anonymised) strings such as shown below. For example, one can replace all words related to locations with the special word “LOCATION”, and respectively all dates with the word “DATE”. The identification of those named entities is carried out using named entity recognition tools such as regular expressions, handcrafted rules, various statistical models such as hidden Markov models and more recently with deep neural network models.

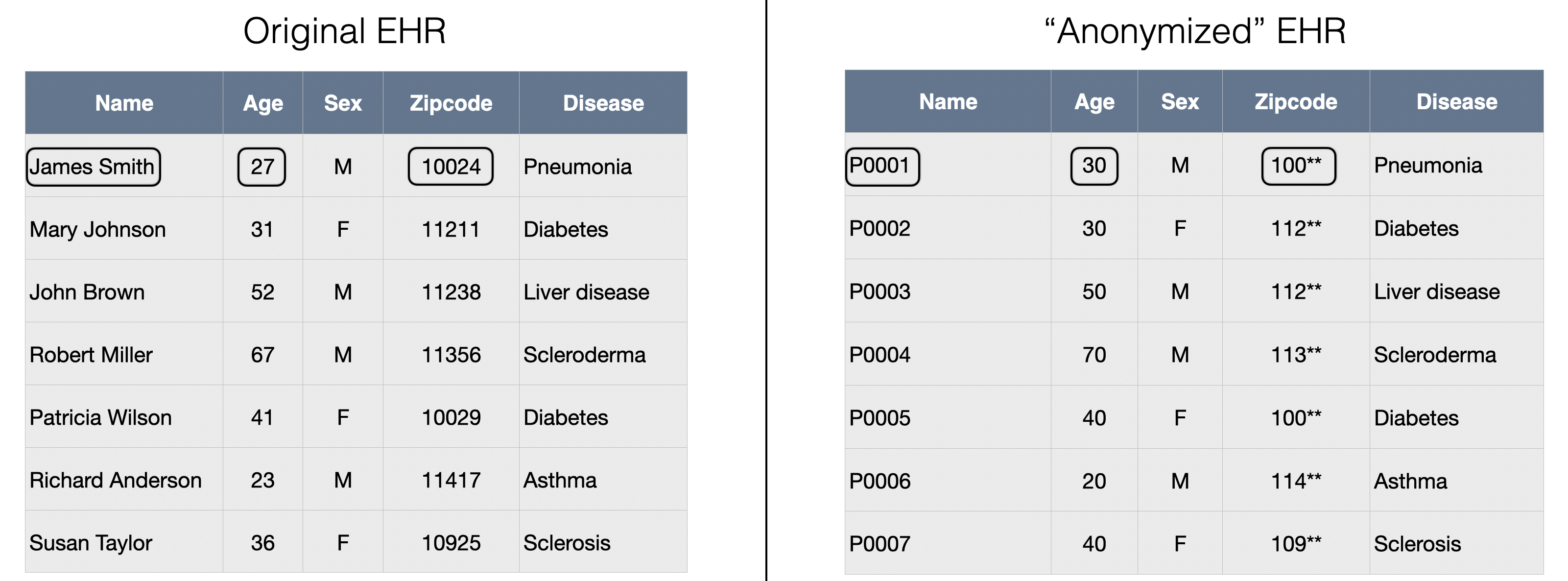

A typical use case is the anonymisation of electronic health records, a made-up example of which is shown below. In this example, the patient names have been replaced with pseudonyms (pseudonymization) and the other fields have been anonymized with various degrees of privacy. Ages have been rounded to the nearest decade and (US) zipcodes have been truncated to the first 3 most significant digits. The disease has not been altered as we might wish to compute some statistics for each disease.

Various rules exist for the anonymisation of medical information, such as those described in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the Guidelines for De-identification of Health Information (HHS.gov 2012).

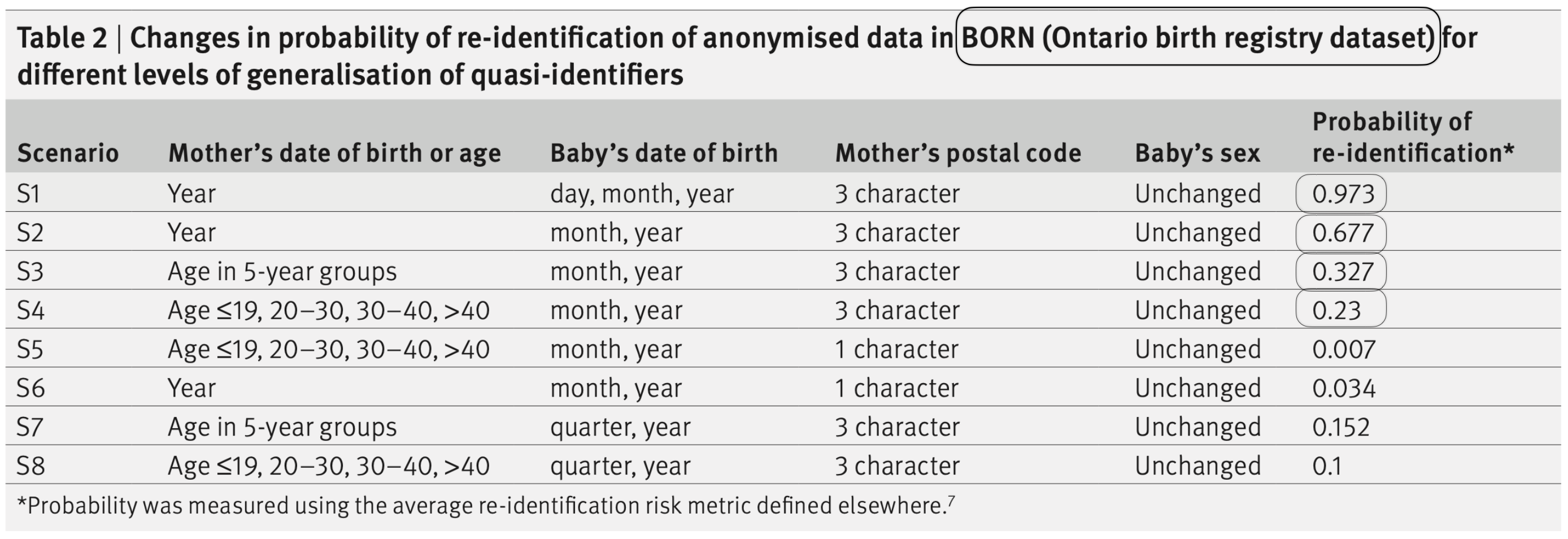

While based on good intentions, data anonymisation techniques offer little guarantee with regard to data privacy. For example, a study by El Emam, Rodgers and Malin, in 2015, showed the probability of re-identification of patients using various scenarios applied to the Ontario birth registry dataset. While retaining sufficient value for data analysis, the risks of re-identification could go from 15 to 97%.

The main issue with the data anonymisation approach is its sensibility to linkage attacks, where one uses some auxiliary information from other sources to compromise the privacy of a given database. Notorious examples abound.

For example, the Netflix Prize dataset contains over 100 million movie reviews from close to half a million users on over 17,000 movies. In order to anonymize the data and release it for analysis, the customer IDs have been replaced with randomly generated numbers. However, since a lot of people reviewing movies on Netflix also post their reviews on the International Movie Database (IMDB.com), Narayanan and Shmatikov showed that very little auxiliary information was needed to de-anonymise a subscriber record from the Netflix dataset. For example, with 8 movie ratings (two of which could be wrong) and review dates that may differ by 14 days, 99% of records could be uniquely identified in the dataset. And with only 2 movie ratings and dates that may differ by 3 days, 68% of records could be identified.

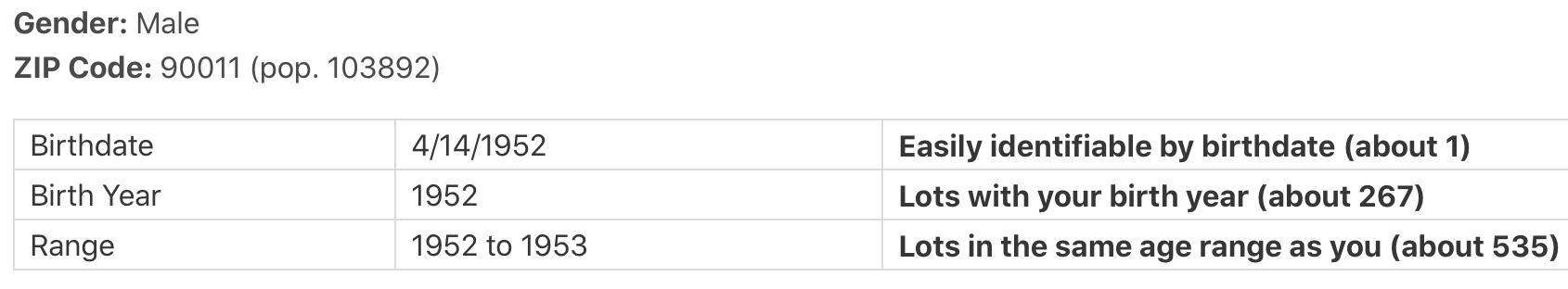

Other linkage attacks of interest are the experiments led by Latanya Sweeney’s DataPrivacyLab.org at Harvard University. One could mention the re-identification of the personal medical records of the Governor of Massachussetts (including diagnoses and prescriptions) in 1997 by using voter registration data, or recovering (in 2013) 90% of the profiles (including names, medical and genomic information, medications and diseases) from the participants in the Personal Genome Project. For that latter attack, the auxiliary information used consisted in voter registration data, mining for names hidden in attached documents and demographics. Using the website aboutmyinfo.org, we can experiment how uniquely identifiable we are based on our date of birth and zipcode, an example of which is shown below.

Clearly, good old fashioned data anonymisation is not sufficient as it does not provide any guarantee of data privacy, and it has been shown in numerous occasions to be very sensitive to linkage attacks.

2. Differential Privacy

The first viable technique that offers some privacy guarantee is called differential privacy. Simply stated, it consists of adding a certain amount of random noise in order to guarantee anonymity to a certain degree (which depends on the amount of noise added).

We will discuss both local and global differential privacy using two test cases.

Local Differential Privacy

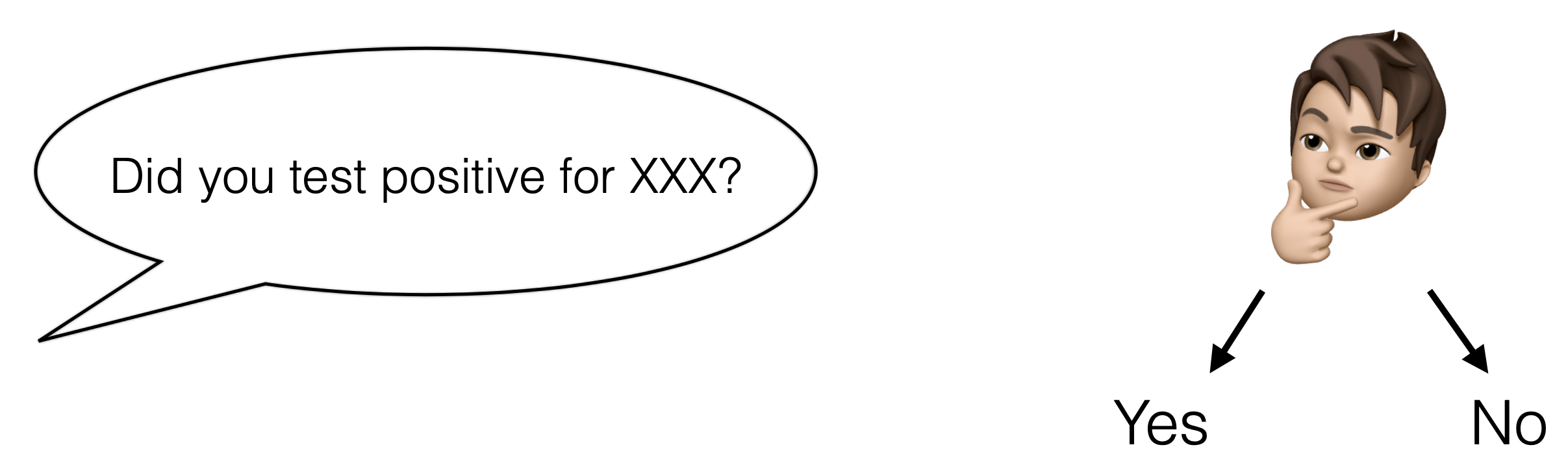

Let us assume that we are conducting a social sciences project in which we want to survey the population for some given sensitive issues like crime or disease. We identified a sample of 100 participants whom we will ask a given question expecting a yes/no answer. Subsequently, we will compile some statistics, such as X% of the population tested positive for XXX.

Unfortunately, and rightfully so, the participants might not wish to answer truthfully to the question. Indeed, we might not trust the database curator that he/she will not divulge our personal information, which in this case is whether or not we tested positive for a particular disease. Even if we trust that person or entity, we might fear that the database holding our responses will be hacked and the data released to the public (which happens often).

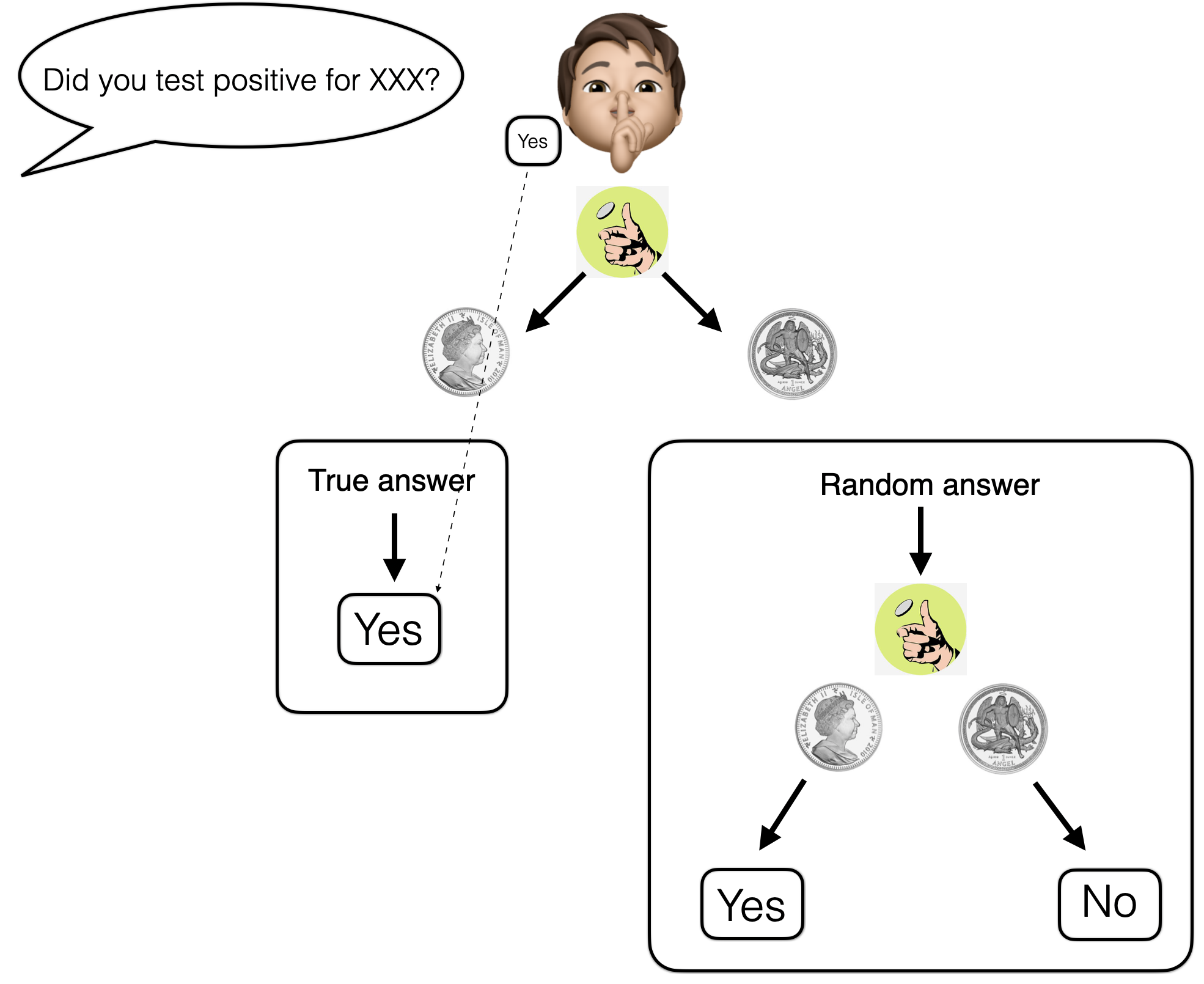

One possible solution is to ask the participants to flip a coin in secret before answering. If that coin toss falls on head, then the participant is instructed to answer truthfully. However, if the coin falls on tail, then the participant is instructed to give a random answer that will be determined by the outcome of a second coin toss (for example YES for head and NO for tail). This protocol is highlighted in the figure below. The key is that the coin toss results (and the number of those tosses) are kept secret (not revealed to the interviewer). The coin tosses could be carried out behind a booth as when voting.

Under a few assumptions (that the participants follow the script, that we have a fair coin

and a relatively large number of participants), the impact of such a scheme will be

that roughly half of the responses collected will be random

(representing roughly 50% yes and 50% no responses) and half of the responses will

represent the true ratio.

This leads to the formula observed_ratio = 1/2 true_ratio + 1/2 random_choice,

and consequently that true_ratio = 2 * observed_ratio - random_choice.

Numerically, if we observe (collect), for example, 35 Yes and 65 No, then

the observed ratio will be 35% (35 Yes out of a total 35 + 65 = 100 responses)

and the true ratio (with the noise removed) will be true_ratio = 2 * 35% - 50% = 20%.

So the observed 35% Yes responses corresponds to a 20% Yes response when the added noise is removed.

At the cost of computing our statistics of interest on effectively only half of the responses, we could guarantee the privacy of the data for each of the respondents. Were the data to be leaked, one could always argue that a Yes answer, for example, is really the result of a second coin toss.

The protocol and a numerical application is represented in the graphic below:

Local Differential Privacy in the industry

Local differential privacy is heavily used by companies such as Apple and Google, for example, in order to learn from the mobile phone usage of hundreds of millions of users. Apple has a very interesting blog (Learning with Privacy at Scale) where they describe clever schemes that make use, among other techniques, of local differential privacy to identify popular emojis, discover new words (in order to improve their auto-correction model) and reveal popular / troublesome web sites.

Global Differential Privacy

Local differential privacy adds noise to every single data point (e.g. on the data from each individual user). With global differential privacy, we assume that the curator of the database is trusted and noise is added to the statistics computed over a number of data points (e.g. user data). By adding noise at the latest possible time in the processing chain (on the result of a query), we can obtain results with a better precision (ignoring less of the information contained in the data).

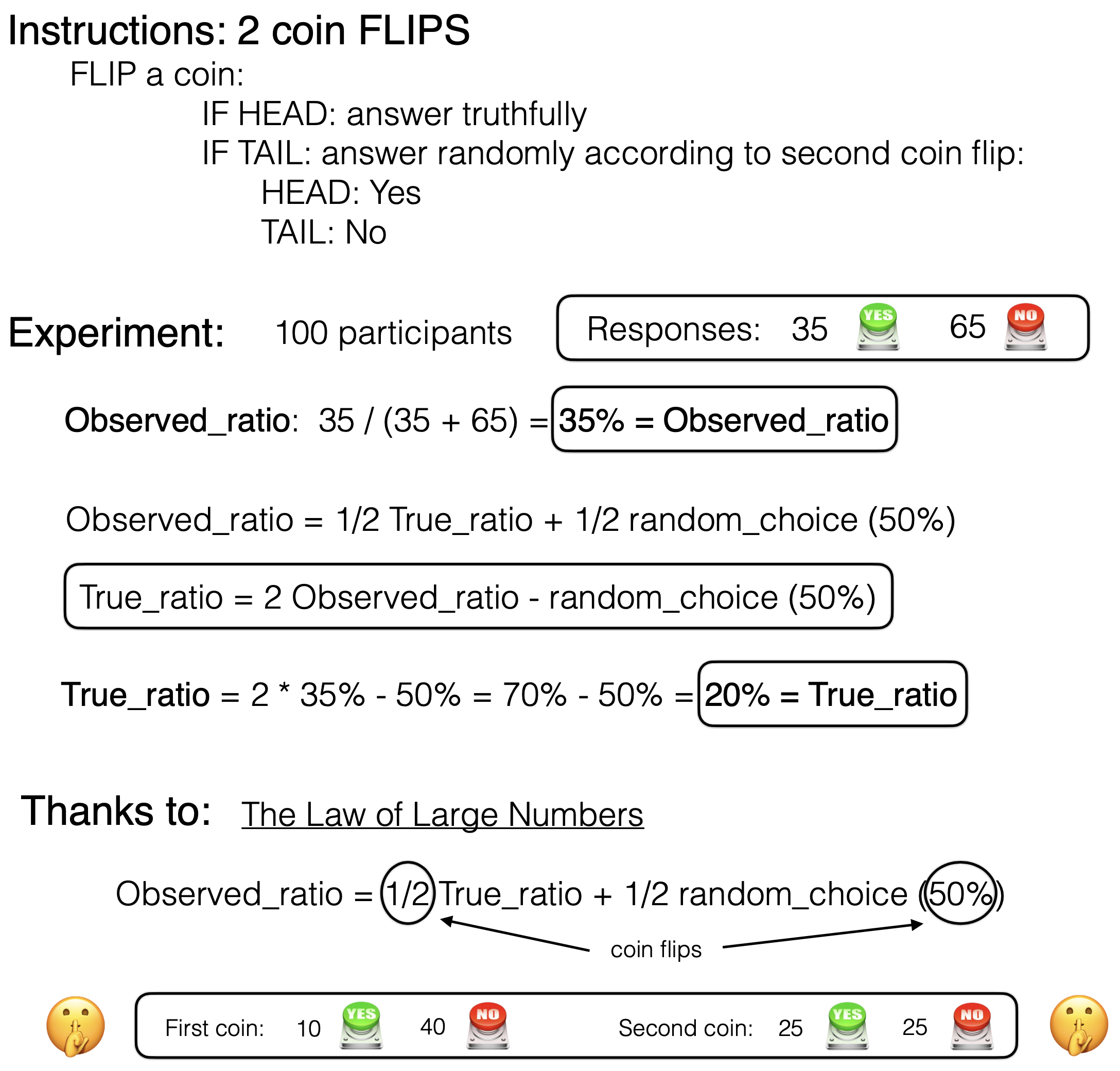

In order to describe the new for global differential privacy, let’s assume we have a trusted database of medical records with information such as patient names, conditions, diseases and medications. As the database curator, we provide an interface (an API) allowing users to query the database for statistics over patients such as the percentage of patients having a given disease. While that API would not allow for querying information about any given patient, using successive queries, one could still infer the condition of a given patient as highlighted in the graphic below. This would be done by using additional information about a given patient (in effect a linkage attack).

This example shows the need for random noise to be added to the statistics returned by the database. How much noise to add depends on the scale of the answer. In the example above, since the answer is a small integer, one should add a small random integer number, for example in the range [-2, +2], to the result of a query.

Formal Definition of Differential Privacy

One original definition of privacy guarantee is:

Privacy is preserved if: After the analysis, the analyzer doesn’t know anything about the people in the dataset. They remain “unobserved”.

In their book “The Algorithmic Foundations of Differential Privacy” (2014), Cynthia Dwork and Aaron Roth define differential privacy as follows:

“Differential Privacy” describes a promise, made by a data holder, or curator, to a data subject, and the promise is like this: “You will not be affected, adversely or otherwise, by allowing your data to be used in any study or analysis, no matter what other studies, data sets, or information sources, are available.

This definition implies that differential privacy should be robust against linkage attacks.

There is also a formal mathematical definition of global differential privacy given by Dwork, McSherry, Missim and Smith in 2006 that is referred to as \(\epsilon\)-differential privacy. The amount of noise to be added to a given statistics depends on a number of factors such as the type of noise added (Gaussian or Laplacian), the sensitivity of the query (a ‘mean’ query has a lower sensitivity, it reveals less information, than a ‘count’ query), and the desired \(\epsilon\) guarantee of privacy. A lower \(\epsilon\) implies less data leakage, but consequently greater variation (in amplitude) in the noise added.

Other uses of differential privacy

Differential privacy techniques can also be used when training deep neural network models in order to ensure that no information can be gained by removing the information of a given person from the training set. In other words, the resulting trained model should be similar whether or not we remove a given person from the training dataset.

For the interested reader, one could mention, for example, the papers Deep Learning with Differential Privacy (Google 2016), and Gaussian Differential Privacy (U. of Penn 2019). Research in the field is still ongoing.

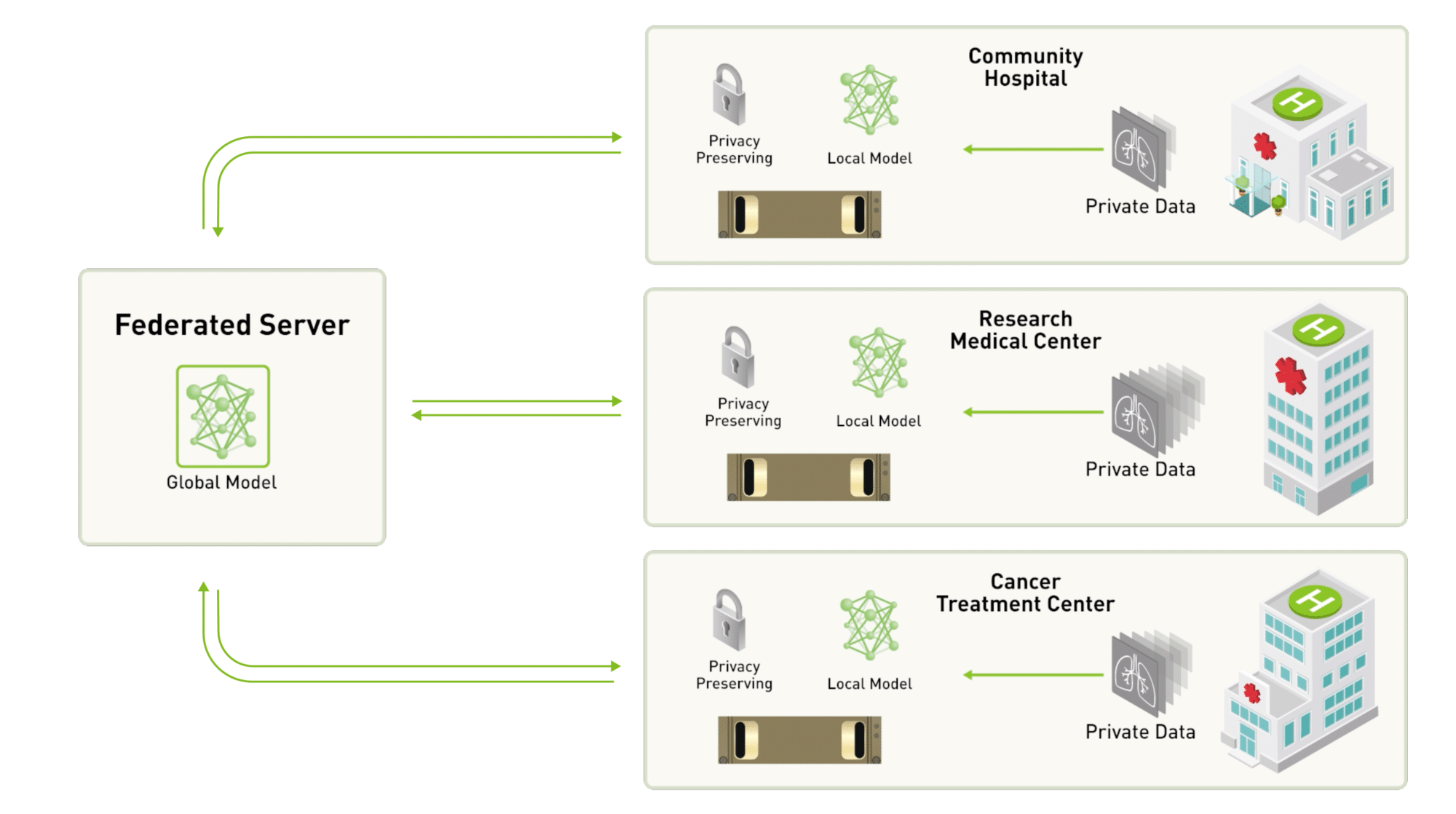

3. Federated Learning

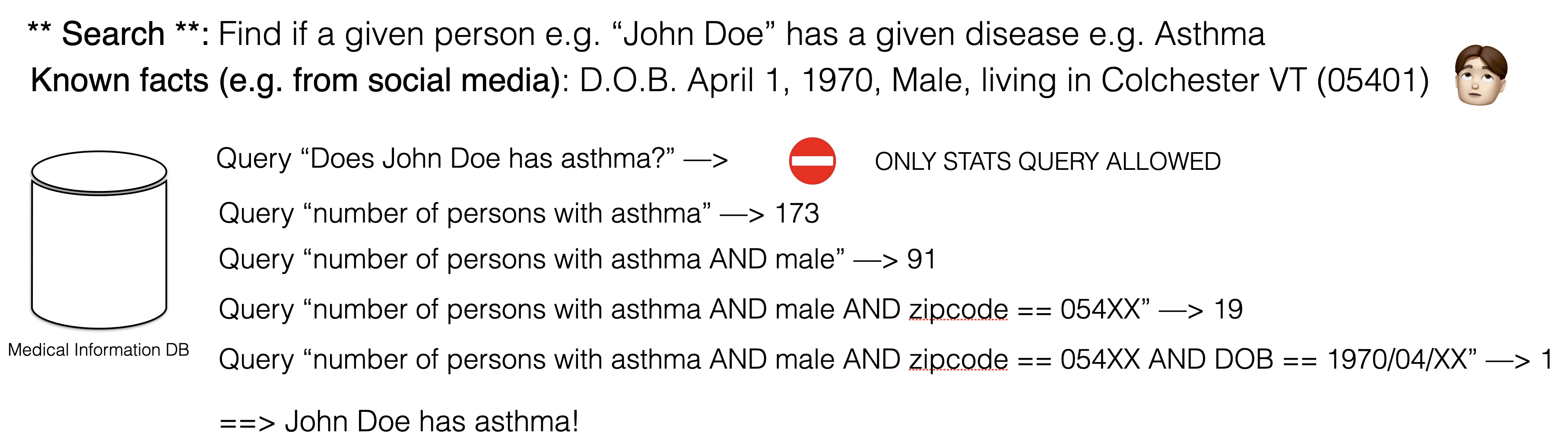

The next technique of interest is federated learning that allows for the training of machine learning models on data which we do not have access to. As with differential privacy, federated learning is heavily used by companies such as Apple and Google in order to leverage the vast amount of information generated by the hundreds of millions of mobile phones running their operating systems.

The idea is train (update) a statistical model on the devices (on the premises where the data resides), and subsequently send the updated model to a server. In this way, the data does not need to leave the devices. For instance, the images that we take on our phones are being used (on device, without leaving the phone) to update the deep neural network models that are used to classify (label) the images in thousands of categories. Additional use cases include updating statistical models for next word prediction, voice recognition, and search query suggestion. The personal data never leaves the phone.

One should note that noise (differential privacy) is usually added to those model updates before being sent to an aggregation server, further ensuring that data privacy is preserved.

As it is often easier to grasp a new concept with some visualizations, the picture below from OpenMined and the online comic from Google should help.

For the interested reader, we note two types of federated learning. In the first kind, we can average (on the server) the gradients computed on the edge devices. This is referred to as Federated Stochastic Gradient Descent (FedSGD). Alternatively, one can train for a few iterations on devices and send the updated model weights to the server to be averaged (Federated Averaging - FedAvg).

Use cases: Transforming healthcare

Of course, it is not only the Apple and Google of this world (with their hundreds of millions of mobile phone users) that can benefit from federated learning. There are other very interesting use cases in domains that truly matter such as in healthcare. In a blog post (2019-10) on Federated Learning, Nvidia presents two such applications.

The first one, a collaboration (video) between Nvidia and King’s College London, aims to simulate access to large, varied and high quality datasets spread over several hospitals. In this particular experiment, they tested with the Brain Tumor Segmentation dataset. A graphic depicting their experiment is reproduced below.

A quote from this blog post summarizes federated learning quite well:

Federated learning decentralizes deep learning by removing the need to pool data into a single location.

A second application, a cooperation between Nvidia and MELLODY (a drug-discovery consortium), aims to use federated learning techniques to leverage drug compound datasets from several institutions (preserving their privacy) in order to improve drug discovery.

For further information on the use of federated learning in healthcare (including challenges), there is a recent paper entitled The Future of Digital Health with Federated Learning (2020-03) as well an article in nature machine intelligence Secure, privacy-preserving and federated machine learning in medical imaging (2020-06). OpenMined.org has several blog posts on use cases for federated learning such as for medical imaging (2019-08) and for pill identification (2020-05).

Use cases: other domains

Other interesting applications are in the financial domain. For example, one could note the recently announced partnership between OpenMined and Gensyn for using federated learning within finance. One goal is to provide a solution for anti money laundering where a model could be trained on proprietary datasets of participating banks.

As mentioned at PriCon conference last September, the United States Federal Government is also using federated learning to build a statistical model for its USAjobs.gov website by leveraging private datasets that reside on (and stay with) the US Army, the US Air Force and the US Navy.

Challenges - Open problems

Federated learning offers some great opportunities in various domains to leverage datasets that would otherwise remain unaccessible in data silos. As a relatively recent technique, there are a few challenges and open problems that one should be aware of. Two recent publications present those issues: Federated Learning: Challenges, Methods, and Future Directions (CMU 2019-08) and Advances and Open Problems in Federated Learning (2019-12).

The CMU paper identifies four main challenges in relation to federated learning, namely: 1. expensive communication, 2. systems heterogeneity, 3. statistical heterogeneity and 4. privacy concerns.

Expensive communication refers to the exchanges that need to take place between the server and the workers (smart phones or organizations). There is a need to develop efficient communication methods for example for sending model weights / gradients. A paper by Google mentions work on improving communication efficiency using techniques such as quantization, random rotations and subsampling.

Systems heterogeneity refers to the differences inherent to the workers. For example, for mobile phones, this would be the amount of storage available, the network connectivity, the level of charge of the battery. Some devices might loose their connection to the server. In a blog post, Google mentions that phones participate in federated learning only when they are not in active use (e.g. when charging at night and connected to a WiFi network).

Statistical heterogeneity of the workers’ data is also a tricky issue. It refers to the notion that the data from the participating devices is not independently and identically distributed (IID). A paper from Hsieh et al. describes the problem.

OpenMined also has a blog that illustrates clearly the issue of non-IID datasets. They present a toy example of a statistical model that is being trained to classify zoo animals using the images that have been taken by a group of friends. The model is built by averaging the models that have been locally trained on each friend’s phone.

In a usual setting where all of the pictures would be pulled and aggregated to form a training corpus, there would be no particular issues. We would probably observe roughly a similar number of pictures per type of zoo animal (e.g. an equal number of pictures of giraffe, monkey, penguin, etc…). However, in the federated learning setting, since models are trained separately on each phone using only the data present on that particular phone, there will certainly exist some annoying types of skew.

The first skew is in the number of images available to train a model. While some of the friends might have taken a lot of images (say a few hundreds), others might have taken only a handful. This represents a two order of magnitude difference in the amount of available data to train a model locally on the phone.

The second type of skew is in the distribution of photos taken per animal type. Some friends might be especially fond of giraffes and have taken almost exclusively pictures of that animal. It would consequently be hard to train a model on such an unbalanced dataset (some types of animals might have no pictures for some of the people).

The last type of concern is data privacy as well security. While the data is not shared, one can still learn some private information from analyzing the model updates (resp. gradients) coming out of a particular device. There will a tradeoff between privacy (e.g. by applying differential privacy on the model updates) and performance of the resulting model.

Open source tools

While the federated learning approach is still relatively new in the open source world, there are tools available such as OpenMined’s PyGrid and TensorFlow Federated.

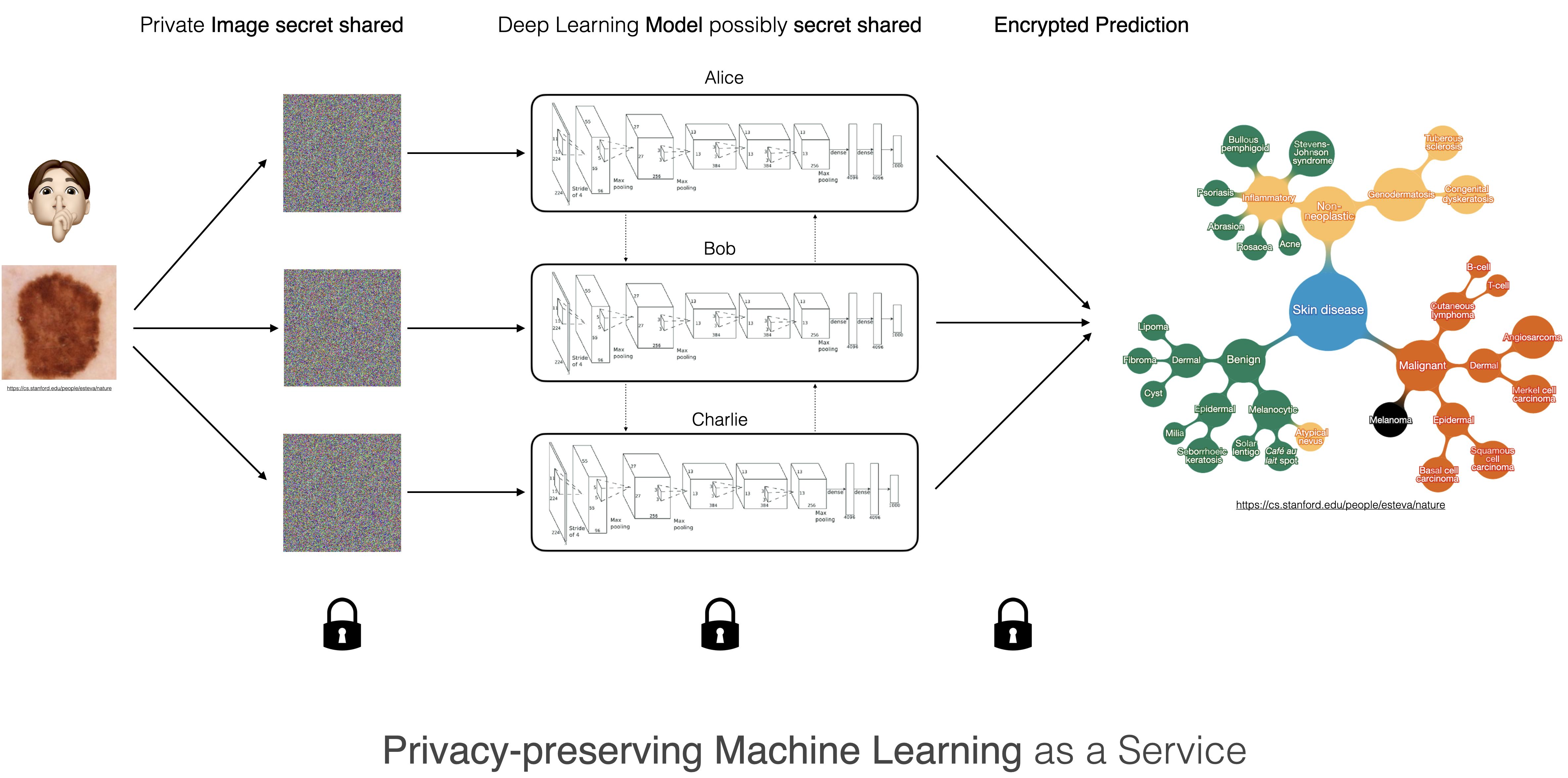

4. Encrypted: Secure Multi Party Computation

With the last two techniques, we are entering the world of cryptography, for an even greater guarantee of data privacy. However, this gain in privacy comes at the cost of increased computing time requirements.

The diagram below highlights a privacy preserving machine learning as a service for a dermatology application. Here we would secret share a picture of one of our lesions, send those shares to the service and get back an encrypted prediction on whether the lesion is malignant or not (source: the images of the lesion and the taxonomy are from Esteva et al. 2017).

Unless one is already familiar with cryptography, it can be a bit puzzling, at first, when trying to understand how one can perform computation on what appears to be, and actually is, random data. In the next few sections, I will attempt to explain how it functions.

It is important to note that the Deep Neural Networks depicted above, and Deep Learning (a.k.a. Software 2.0) in general, make use of a surprisingly small number of types of operations. A typical network performs little more than additions, multiplications and thresholding at zero (ReLU). So if we can figure out how to perform those operations on encrypted values, we are good to go.

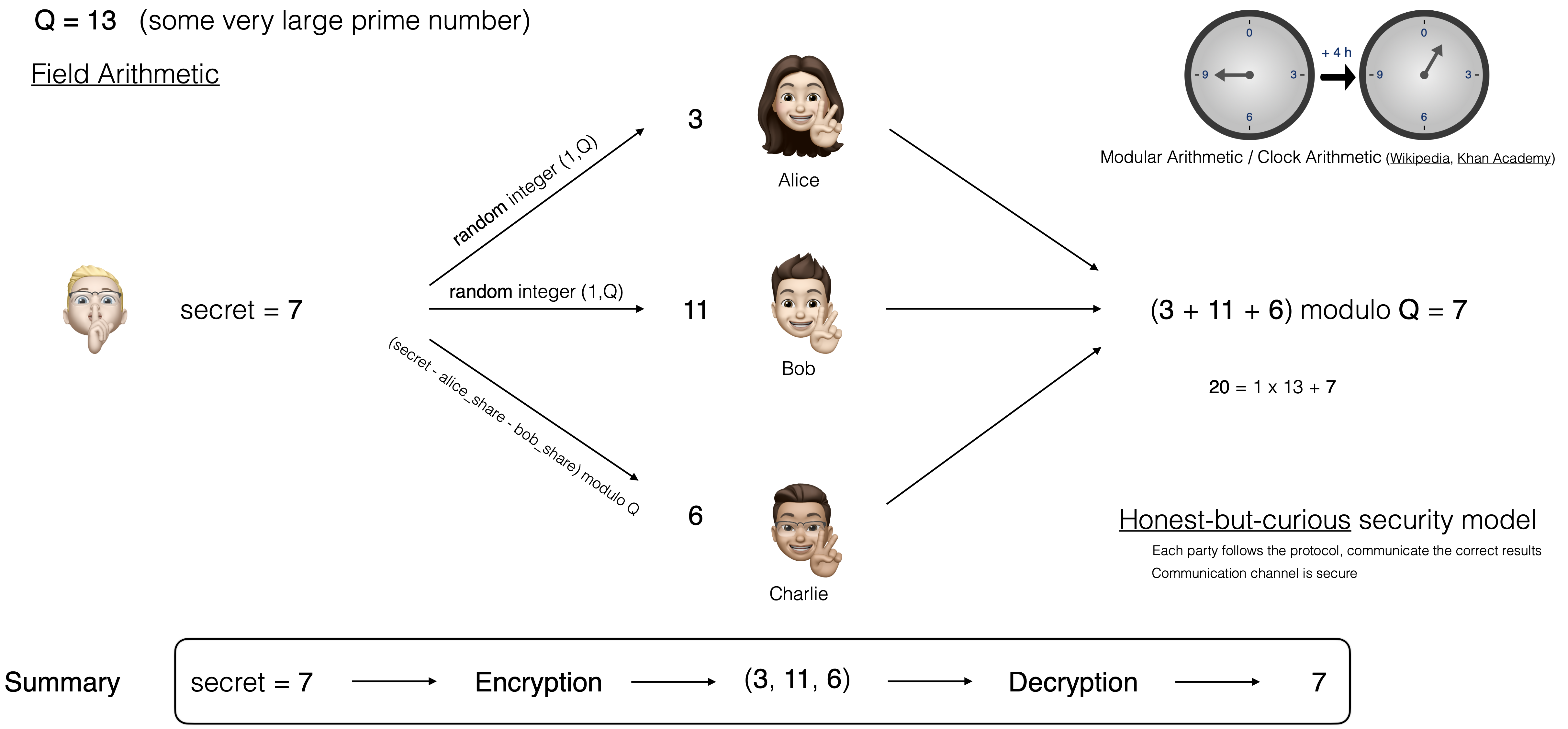

Additive Secret Sharing

The first step is to understand how one can secret share an image among several parties. Recall that, for a computer, an image is represented as a two dimensional matrix of pixel values (or more accurately a 3 dimensional (height, width, RGB) tensor of values). So if we can understand how one value is secretly shared, we can generalize and comprehend how an image can be shared without revealing any information.

The problem at hand is to figure out a way to store / share a secret. That secret could be a safe combination, a numbered bank account, some missile launch codes, encryption keys, or the pixel values of an image. The technique used is called additive secret sharing (secret splitting) and it makes use of modular arithmetic (which could also be referred to as clock arithmetic) and belongs to the domain of field arithmetic.

A simple example is provided in the figure below.

Let us assume we have a secret (the number 7 in the example above) that we wish to share (store safely)

between three parties (Alice, Bob and Charlie). Each of these persons will be getting a share of the secret.

First we need to choose some very large prime number that we will refer to as Q.

In our simple example, we will set Q = 13.

Next we generate two random numbers between 1 and Q that we will be sending to Alice and Bob.

And finally a third value that is set to (secret - alice_share - bob_share) modulo Q.

That last share is sent to the third party (here Charlie).

In our simple example with a secret value of 7, if we assume that the first two

random values generated are 3 and 11, then the last share will be set to

(7 - 3 - 11) modulo 13 = (-7) modulo 13 = 6.

So in that instance, the secret 7 will be represented with the 3 shares (3, 11, 6).

Note that those values are actually random and do not reveal any information when taken in isolation.

The next time we share a value 7, we might get different random values, as for example

(4, 8, 8).

In order to recover our secret, we simply sum the shares from each of the parties

and perform a modulo operation.

Explicitly, for our example, we retrieve our secret with (3 + 11 + 6) modulo 13 = 20 modulo 13 = 7.

This scheme corresponds to an honest-but-curious security model. It assumes that the parties (Alice, Bob and Charlie) follow the protocol (e.g. they do not alter the share they are given) and they do not attempt to find out the shares allocated to the other parties.

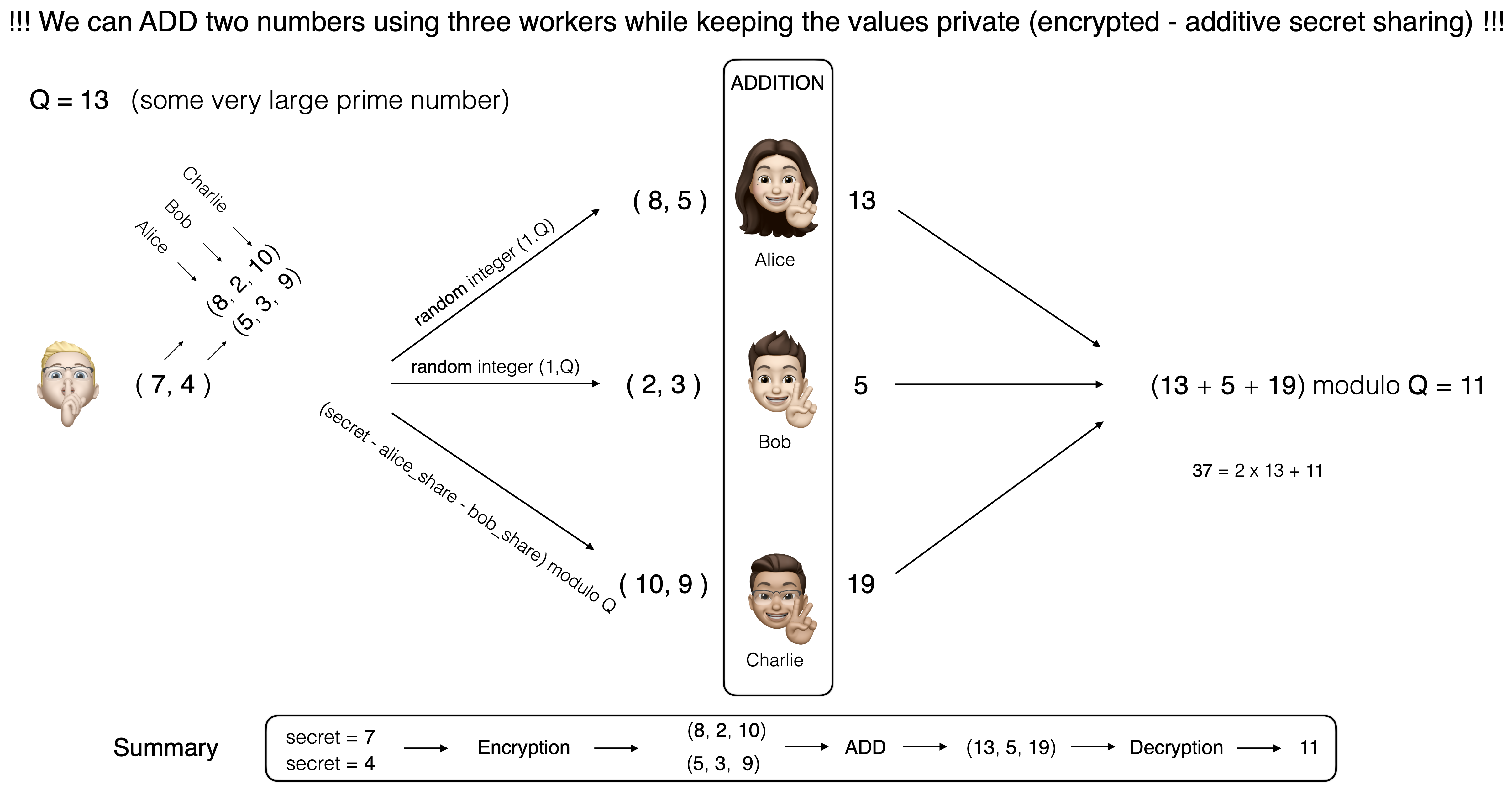

Addition operation on secret shares

Now that we understand how to secretly share a number among several entities, we need to figure out how to perform arithmetic operations on those numbers. The first (and simplest) operation is the addition of two values.

The scheme is depicted in the figure below:

Let us assume that I have two secret (personal) numbers (here 7 and 4),

and I wish to perform a summation over those numbers using three entities represented

by Alice, Bob and Charlie. The first step is to encode those two numbers using

the additive secret scheme we have seen in the previous section.

Depending on the state of some random generator, the numbers 7 and 4 could be

represented, for example, with the shares (8, 2, 10) and (5, 3, 9) respectively.

(We can verify that indeed (8 + 2 + 10) modulo 13 = 7 and (5 + 3 + 9) modulo 13 = 4).

Next we sent the shares to each entity. Alice gets (8, 5), Bob (2, 3) and Charlie (10, 9).

Each of them performs an addition on the random numbers they are assigned to.

In order to get the result of that summation, we get the computation results from

each entity and perform the decoding as in the previous section.

In that particular example, we get (13 + 5 + 19) modulo 13 = 37 module 13 = 11.

So we get that the result of the summation of 7 and 4 equals 11,

which is the correct answer.

Addition of two integers (positive or negative)

The scheme we have described above is fine for adding positive integers. However, in the context of deep learning, we are really interested in performing operations on real numbers (e.g. -2.7325, 3.167).

Let’s first consider the summation of positive and negative integers with the diagram depicted below.

The “trick” is to take a larger number Q and set that half of the range of values

([0, Q/2]) will represent positive integers and the remaining values will

encode negative integers.

The encoding step remains the same. When decoding, we simply check whether the

resulting value is greater than Q/2. If it is, then we substract Q.

Numerically, with above example and Q set to 23, the numbers 3 and -5

are encoded with (10, 18, 21) and (22, 7, 12) respectively.

The sums of the shares yield (32, 25, 33).

The sum of those shares modulo Q gives (32 + 25 + 33) modulo 23 = 90 modulo 23 = 21.

Since 21 is greater than Q/2 (11), we subtract the value of Q from that result

and get 21 - 23 = -2. So we performed a secure multi party addition and got that

3 + (-5) = -2.

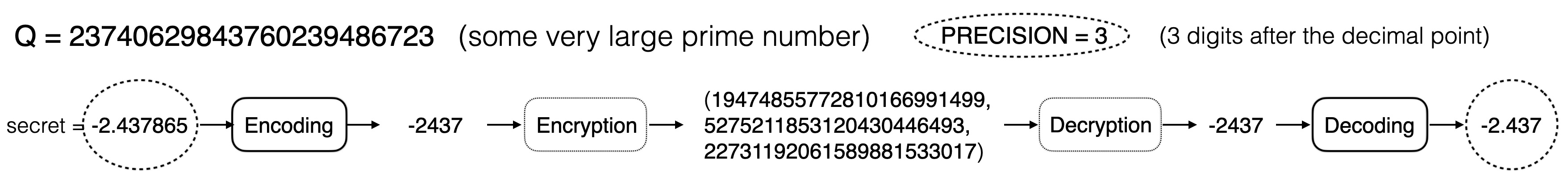

Addition of two real numbers

Note that the additive secret sharing schemes only works with positive integers

ranging from 0 to Q-1. Therefore, in order to deal with real numbers such as

-2.437865, we need to proceed with fixed precision encoding.

The process is illustrated with example below:

This time, we really proceed with a very large prime number for the value of Q.

We decide that we will consider only 3 decimal values (3 digits after the decimal point).

Consequently, for a number such as -2.437685, we will only be working with the

approximation up to 3 decimal values and multiply the result with 10^3.

So -2.437685, will be encoded as -2347.

The rest of the processing proceeds as usual. When decoding a result, we will

take care to divide by 10^3 (in the case of an addition).

Other operations (multiplications, …)

The native operations in the secret sharing protocol are additions and multiplications. We saw how to perform additions on encrypted (secret shared) numbers in the previous sections. The multiplication is a bit more complicated and costly as the workers (Alice, Bob and Charlie) need to communicate between them (secret sharing some of their values with the other members) in order to complete the multiplication. One way to perform the multiplication is to by using the SPDZ protocol. To understand how it functions, once could refer, for example, to some of Morten Dahl’s blog posts.

As mentioned previously, Deep Learning models use a surprisingly small number of types of operations. Besides additions and multiplications (which were described above in the context of multi party computation), deep neural networks need the ability to threshold values at zero (ReLU), as well as make use of the sigmoid, tanh and exponential functions.

The solution for sigmoid, tanh and exponential is to use an approximation of those functions

expressed as a combination of additions and multiplications.

This is done using Taylor series expansion.

For example, for a value of x close to zero, the exponential function can be

approximated with the third degree polynomial:

\(exp(x) = 1 + x + \frac{1}{2}x^2 + \frac{1}{6}x^3\)

.

For the interested reader, a great resource to really grasp this notion of Taylor series is the course Calculus Single variable given by Robert Ghrist.

Counterintuitively, simple (non differentiable everywhere) functions like thresholding a value at zero (ReLU), (e.g. comparing two values) is very hard to perform on encrypted data. One solution to this problem is to replace those simple functions with more complicated but differentiable ones for which we can make use of Taylor Series expansions. Concretely, this means replacing ReLU with sigmoid and replacing max pooling with average pooling (in order to avoid the comparison of values which is hard to perform on encrypted values).

Issues, avenues, …

We are still in the early stages of seeing Multi Party Computation being deployed for real problems.

The issues and avenues for further improvements, that are currently being worked on, include, among others, the communication and computation costs. Communication cost refers to the synchronisation steps that need to take place between workers for the completion of multiplication operations.

The processing time is still orders of magnitude slower when compared to the non-encrypted world. As such, every aspect of a deep learning model needs to be looked at to ensure efficient computations. This includes, among others, opting for suboptimal optimizers (momentum SGD instead of Adam), various tricks to share matrices in the classification heads (the last few dense layers of deep neural network), and in general designing / altering functions for efficient computations in the encrypted domain.

Open source tools

Open source tools for developing secure multi party computation applications include solutions from OpenMined as well as the CrypTen library from Facebook Open Source.

5. Encrypted: Homomorphic Encryption

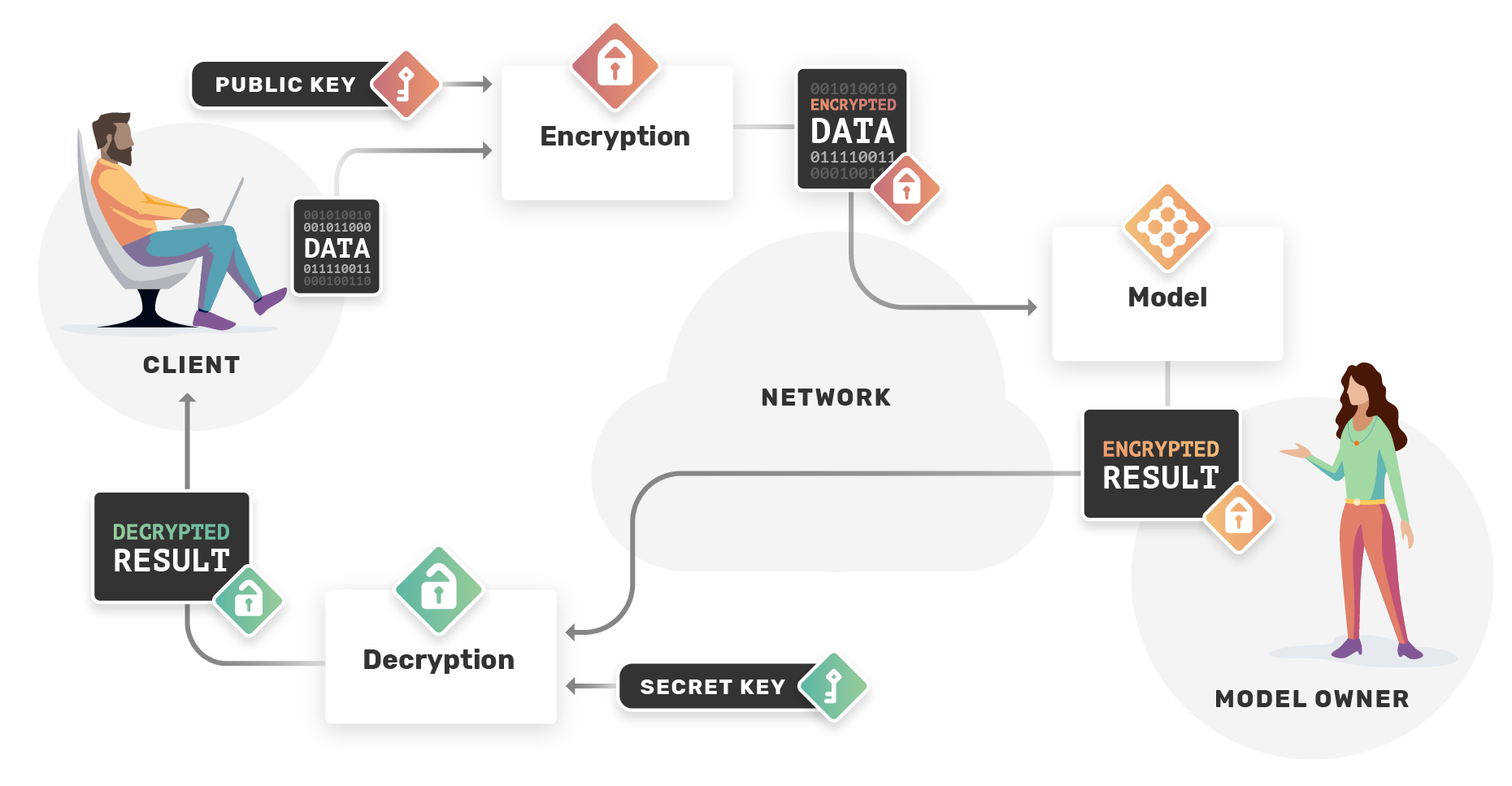

The last technique offering the best privacy guarantee, at the cost of a high computation overhead, is Homomorphic Encryption that performs operations on encrypted data. The process is illustrated in the graphic below coming from an OpenMined’s blog post.

The field of Homomorphic Encryption (HE) is relatively quite new. In 2009, Craig Gentry, in his PhD thesis, proposed the first fully homomorphic encryption scheme, a crypto system supporting arbitrary computation on ciphertexts.

In a recent presentation at PriCon 2020, Kristin Lauter mentioned that the HE scheme, in 2009, was in the order of \(10^{12}\) slower than computing on clear (non encrypted) values. However, since then, the community has proposed many new ideas to make the process faster. In 2019, fully encrypted computation using homomorphic encryption was in the order of \(10^{4}\) (or 10,000 times) slower. With such advancements, the technology becomes feasible for some real world applications. It is estimated that in 2021 (Microsoft’s Project HEAX), with the use of special hardware (GPU / FPGA and ASIC), homomoprphic encryption could become only two order of magnitudes (100 times) slower than computing on non-encrypted values. This would definitely open many new opportunities for real world applications.

The field is definitely quite new with new schemes being released and adopted in the last few years (e.g. CKKS scheme 2017).

Test cases

Recently (2019), IBM had a project with a Brazilian bank in order to bring homomorphic encryption techniques to the financial world (paper).

Tools - references

- Blog posts:

- Open source tools:

- Palisade: widely used Lattice Crypto Software Library - DARPA funded - supports leading homomorphic encryption schemes (BGV, BFV, and CKKS, TFHE)

- SEAL (Microsoft): widely used open source library from Microsoft that supports the BFV and the CKKS schemes

- HElib: early and widely used library from IBM that supports the BGV scheme and bootstrapping

- Tutorial:

Final word

There is great potential for all those privacy preserving machine learning techniques (differential privacy, federated learning, multi party computation, homomorphic encryption) and it is quite exciting to keep up with the new developments in that relatively new field. Looking forward to The Private AI Series of lectures starting in January 2021…

Resources

- Andrew Trask’s 2 minute video introducing The Private AI Series courses.

- Courses: Secure and Private AI (Udacity - OpenMined), The Private AI Series (OpenMined, Facebook AI, University of Oxford)

- Open Source Community: OpenMined.org: Lowering the barrier to entry to privacy preserving machine learning technologies

- Tools: OpenMined, PySyft, PyGrid, TensorFlow Federated, CrypTen, TenSEAL, SEAL

- Homomorphic Encryption standardization: homomorphicencryption.org

- Conferences: PriCon 2020, PPML @ NeurIPS